Jewish History in Lüneburg

The history of Jewish life in Lüneburg can be divided into three phases:

In the late Middle Ages there was a first Jewish community. To this day, we know almost nothing about its members. All traces of their community were destroyed. This first phase ended with a plague pogrom in 1350: the Jews of Lüneburg were robbed and slain by their Christian neighbors. Only a few managed to escape.

In the late Middle Ages there was a first Jewish community. To this day, we know almost nothing about its members. All traces of their community were destroyed. This first phase ended with a plague pogrom in 1350: the Jews of Lüneburg were robbed and slain by their Christian neighbors. Only a few managed to escape.

Around 1700, a new Jewish community was founded. Initially, it only consisted of three to five families, then grew to nearly 200 members in the 19th century, and was destroyed during the Nazi era. The focus of our website is on the 200-year history of this community. Its members played a significant role in the long history of the Hanseatic town of Lüneburg. Descendants of the town’s Jewish families all over the world as well as researchers in Lüneburg have kept the history of these Jewish families alive, so that there is a large basis of official documents as well as private memories and pictures.

Shortly after the end of World War II, in 1945, a third Jewish community was established. It was formed by several hundred Holocaust survivors, so-called Displaced Persons. For most of them, Lüneburg was only a brief stopover on their way to emigration, but an important part of their lives nevertheless. Research on their history has only recently started. Thus, the website’s documentation relating to postwar Jewish life is still at a very early stage.

There has been no established Jewish community in Lüneburg since the late 1950s.

13th/14th Century

The beginnings of Lüneburg's medieval Jewish community are largely obscure: in 1288, a source mentions for the first time a "platea judeorum" or "Jodenstrate" below “Kalkberg”. It seems therefore that Jews had been living in the town for some time. In 1350, almost all of Lüneburg’s Jews were robbed and murdered in a plague pogrom by their Christian neighbors. Only a few were able to escape. For the next three hundred years, no Jews settled permanently in the town. But the street "Auf der Altstadt", where the medieval synagogue also stood, was still known as “Judenstrasse” until about 1800.

1680-1945

The road to the second Jewish community began in 1680, when Ernst August, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, established textile manufacturer Jacob Behrens in Lüneburg as one of his "Schutzjuden." (“protected Jews”). From the 14th to the 19th century, German rulers granted this status to Jewish merchants, in order to profit from their revenues and control the settlement of Jewish families. In return for the payment of high protection fees and adherence to strict restrictions of mobility, the “Schutzjuden” received a certain degree of external protection and privilege over other Jews.

In the beginning, the citizens of Lüneburg strongly resisted the duke’s attempts to install Jews in their town. Therefore, up to the early 1800s, there were never more than five Jewish families in Lüneburg. For more than a hundred years, Jews in Lüneburg were not allowed to acquire real estate. And it was only in 1823 that the Lüneburg magistrate finally granted the Jewish community their urgent wish to establish a Jewish cemetery.

With the beginnings of Jewish emancipation in the 1840s, a new phase began. “Emancipation” in this context meant the abolition of discriminatory inequities applied specifically to Jews, the recognition of Jews as equal to other citizens, and the formal granting of the rights and duties of citizenship. Jewish emancipation brought an end to the payment of protection money and other forms of harassment. In 1843, three long-established Lüneburg Jews were granted citizenship. Soon, many more Jewish families settled in the town. At first, they were mainly active in the banking and textile business, but gradually other trades and professions were added.

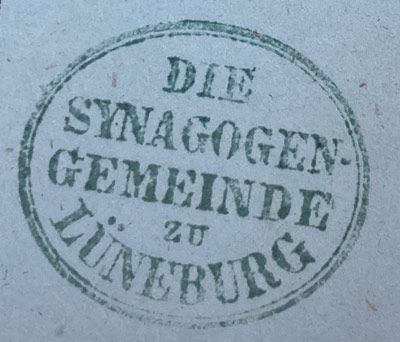

The Jewish community continued to grow steadily, from 48 members in the year 1848 to 130 members in the 1870s. Around the year 1905, the peak of almost 180 members was reached. Lüneburg never had its own rabbi. But since the 19th century, there was a permanently employed Jewish teacher. For two centuries, the congregation used various large rooms in the old town as prayer halls. In 1894, the magnificent building of the large synagogue was inaugurated.

The period up to World War I was a time of increasing social recognition and economic advancement for the Jews of Lüneburg - as for German Jews in general. There were Jewish bankers, merchants, lawyers and doctors as well as workers, clerks, craftsmen, cattle dealers, housemaids and second-hand dealers. Jewish children attended state schools. Jews were active in sports clubs, political movements and social or cultural associations.

After 1918, however, antisemitism also made itself felt more frequently in Lüneburg: there was graffiti and vandalism at the synagogue, culminating in a bomb attack on a Jewish lawyer in 1922. In the 1920s, the devastating social and political effects first of hyperinflation and later of the global economic crisis hit the town. The difficult situation forced some Jewish citizens to move to larger cities or to emigrate.

At the same time, as a result of political turmoil abroad, many Jews from Eastern Europe came to Lüneburg between 1900 and 1925, mostly from the Austro-Hungarian (and later Polish) region of Galicia. These often rather poor "Eastern Jews" and the members of the existing Jewish community were separated by different interpretations of religion as well as social and cultural differences.

When the National Socialists came to power in 1933, 114 persons of Jewish origin were counted in Lüneburg. In 1937, there were only 38 of them left. National Socialist disenfranchisement, growing impoverishment and strict exclusion made many Jews leave town, especially the younger ones. Increasingly isolated and ostracized at school and at work, expelled from the Nazi "people’s community," they no longer had a future here. They moved to larger cities or emigrated. "Aryanizations" ensured that in the fall of 1938, there were only two Jewish business owners left in Lüneburg. During the November pogrom of 1938, their businesses were destroyed. All Jews still living in the town were harassed, and their homes were attacked and partially destroyed. The Jewish men were arrested and deported to Sachsenhausen concentration camp.

In the years that followed, a few more Jewish families were able to emigrate under great pressure. But some of them, especially older people, did not make it. In 1941 the deportations "to the East" began. The last Jewish citizens of Lüneburg were almost all murdered or died from disastrous conditions in Nazi ghettos and camps. Towards the end of the war, there was no longer any Jewish life in Lüneburg.

1945-1955

The proximity of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp and the fact that Lüneburg had remained largely undestroyed during the war made the town a place of temporary refuge for concentration camp survivors. Most of them were Jews from Eastern Europe: they could not and did not want to return to their home countries. Starting in the summer of 1945, a new Lüneburg Jewish community of "DPs", Displaced Persons, was thus formed, which at times had several hundred members. For them, Lüneburg was only a transit station on their way to America, Australia, Scandinavia or Israel. The Jewish community quickly disbanded, and by the mid-1950s the last members had left Lüneburg or died here.